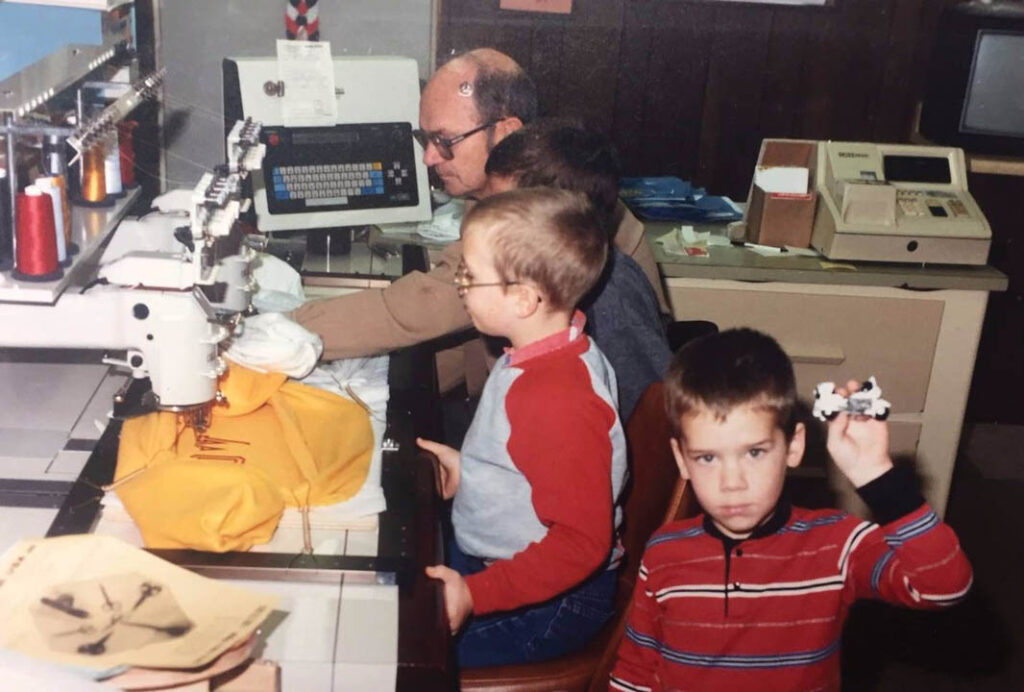

Our print shop, P&M Apparel, is third-generation family-owned, starting with my grandparents in the basement of their house and a two-head Barudan, with hopes to make $300 a week. My mother took it over 10 years after its inception. She added screen printing and heat presses to our decoration methods, but more than that, she added financial organization, staffing, structure, and business goals to a mom-and-pop shop that was quickly evolving into a respected small business. P&M Apparel has grown from the basement to an 8,000 square-foot facility with 16 employees and customers all over the world (126 countries just last year).

When she was ready to retire two years ago, my brother and I had already been working there for years and had already declared our intent to take over, but there was never pressure from the previous two generations about keeping the business going. If anything, the pressure was coming from us, honoring a legacy established by our grandparents and parents of nearly 40 years in business, and making sure we were leaving a legacy for the future of P&M Apparel.

First steps

Our “first step” when we started planning for succession was looking for books and articles that would help guide us on how to pass the torch. When my mom took over for my grandparents, there wasn’t a lot of formal transition: she kept them on payroll to take care of them, and they would come in to work when they were bored at home. The most formal part of the transition was purchasing the building from them, a very simple bill of sale of the company, and acquiring a lot of debt that my mom had to address.

By the time she was ready to retire, we were a thriving business with a full staff and a lot of valuable “blue sky.” Whatever that means. Because I’m going to cut to the chase here: There isn’t a lot of great information on how to transition a business, while keeping it in the family, while no one has a background in business, while everything is amicable and all parties are well-equipped and ready, without giant stock profiles and boards because we’re still a relatively small business, and while making sure all parties are taken care of for the future.

So, our actual first step was talking — a lot. When my mom took over, she felt very stuck, like it was her or nothing. She didn’t want my brother and me to ever feel like we couldn’t leave, and made that clear from our first day of employment. Family matters more than business, and if the business was affecting our relationships, she wanted to make sure there was a clear path to an exit if necessary, one that she never felt she had.

Neither my brother nor I had intentions to take over: I was planning on being a big shot graphic designer working at a magazine house or design firm somewhere very metropolitan, and my brother was planning on going into social work. I happened to join P&M when my company had layoffs and they needed a designer; my brother joined as a temp when I went on maternity leave.

On our own paths, we realized we weren’t printing shirts; we were helping tell stories for clients and had opportunities to make a difference in our community in a way no other job had offered. It took longer to convince our mother that we really wanted to take over than it did to convince ourselves that this is where we belonged. So we talked a lot.

We talked about why P&M is important to us. We talked about where we wanted to take P&M in the future. We talked about what business looked like in the past and what we would have done differently. We talked about how we wanted staff to evolve and what made our business different than our competitors. We went through “traction” together and talked about our core values. When we butted heads at work (this was mostly me, the bull-headed eldest daughter coming out), we talked about our reasoning for coming to different conclusions.

We talked about how much our bills were each month, a monthly payment for selling the company, how to plan for pay raises and bonuses, when to buy new equipment, and whether to use cash or get a loan. We talked about customer loyalty, why they come to us, and how to preserve that relationship building.

We talked about pricing and overhead, when to give in to a cranky customer, and when to stand your ground. We talked about looking at the bigger picture of the company when every other employee will be looking at a much more zoomed-in perspective. We talked about leaning on each other when it gets hard and remembering that family is more important than business.

Timelines & paperwork

Step one: talk. Step two: lay out a timeline. Knowing when things would go into motion not only helped us plan accordingly, but it also helped our staff in the transition. The three of us had a general idea, but through our conversations, it became clear what the timeline for transition would look like. There was a clear moment when our mom backed away from the management side of things and focused on the accounting side.

From then on, most decisions were made by my brother and me unless they involved money. Then there was a clear moment when even money decisions became our responsibility. There was a moment when she started coming into work less often and moving to more of a part-time role.

Finally, there was a moment where the papers were signed and the business was ours. This was probably the most anticlimactic of all the moments, and the only real time we had a lawyer involved. The lawyer’s responsibility was to draft up a transfer of all titles and paperwork, create formal shares and the division of the shares, develop the payment schedule for paying for the business, and file all details with the state.

Some businesses may need lawyers to play more of a mediator role in determining what’s fair for both parties, and that’s a great way to protect your investments and your relationships. For us, we had invested a couple of years talking through everything, so we felt comfortable having one lawyer and using them just for the formal business stuff that was way over our heads.

The work of generations

There is a weight that comes with taking over the family business that my brother and I didn’t feel, even when we were managing the company. I think the first time I felt that weight was when a customer read through our website bio after not getting the basketball jersey number his kid wanted, and on the phone, told me my grandparents would be ashamed of how I’m running their business into the ground. Was he being wildly dramatic, and it wasn’t at all true? Sure.

There is a weight that comes with taking over the family business that my brother and I didn’t feel, even when we were managing the company. I think the first time I felt that weight was when a customer read through our website bio after not getting the basketball jersey number his kid wanted, and on the phone, told me my grandparents would be ashamed of how I’m running their business into the ground. Was he being wildly dramatic, and it wasn’t at all true? Sure.

Did it still make me spiral, worrying that I was falling short of honoring the legacy of the two generations that built this company? Also yes. Second-generation family-owned is a cool thing, but at the third generation, it feels like the pressure is on, and it’s not just a fluke.

We are now the people for whom the buck stops. We are responsible for putting food on our employees’ tables. We are responsible for client satisfaction. It’s a heavy burden, and my brother and I have a running joke that we schedule our panic attacks at 2 a.m., because that’s the only time we’re available. But we have each other, and that’s been a big support in taking over P&M; one of us can always pick up where the other falls short.

We don’t know if the fourth generation will take over or if we will be the third and final, but we don’t plan to put any pressure on them. It helps that the youngest is 6, and there’s no way they’re in a position to take over right now anyway. For now, we’ll just run P&M with the legacy of the past and future in mind.