Paper! The thin material we encounter every day in some form or other is produced by pressing together moist fibers of cellulose pulp derived from wood, rags or grasses, and drying them into flexible sheets. It has so many uses, including writing, printing, packaging, cleaning, and hundreds of industrial- and construction-related processes that it’s impossible to imagine a world without paper.

A Brief History

The word “paper” is derived from the Latin word papyrus-a thick, paper-like material produced from the pith of the Cyperus papyrus plant. Papyrus was used in ancient Egypt and other Mediterranean cultures for writing, but the oldest known archaeological fragments of the immediate precursor to modern paper date to the Second Century BC in China. Before the industrialization of paper production, the most common source of fiber was from rags made of hemp, linen or cotton. With the introduction of wood pulp as a fiber source in 1843, paper production was no longer dependent on recycled rags.

Today, there are countless varieties of paper used for printing. The characteristics of these substrates vary substantially and affect the vibrancy, contrast, texture and durability of the print.

Wood Pulp

Many papers start out as trees. They are made from wood, which contains cellulose and lignin (an organic polymer). To make pulp from wood, a chemical pulping process dissolves lignin in a cooking slurry so that it may be washed from the cellulose to preserve the length of the cellulose fibers. The pulp fibers are poured onto an open mesh screen called a “deckle” and then pressed and dried into paper. When pressed together, the fibers interweave at a microscopic level producing a smooth, level surface.

Standard Office Bond

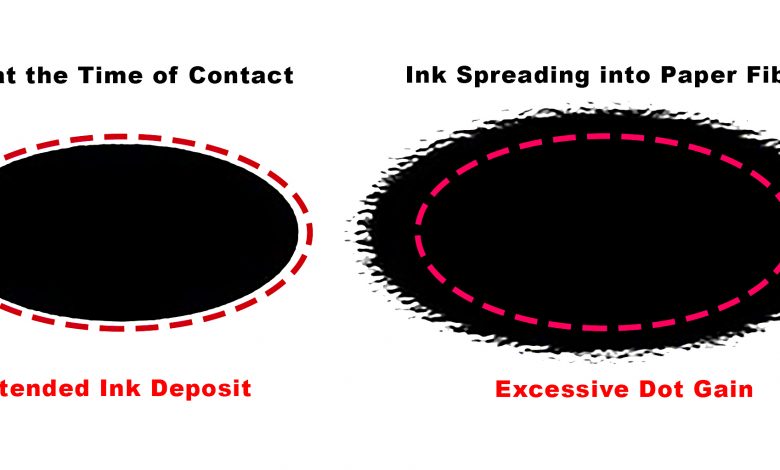

Probably the most common paper you’re likely to encounter-I’ll call it “Standard Office Bond” (SOB)-is a relatively inexpensive substrate and is normally used with the dry toner-based media typically used in copy machines and laser printers (see Figure 1). This paper does not usually get wet. Because of its porosity, moisture tends to wick through the fibers, and spread. Using SOB for inkjet printing absorbs pigment, producing fuzzy edges, poor color gamut and muddy colors. In addition, large ink deposits from graphics or photos soak the paper fibers, become swollen with moisture and then contract, resulting in waves and buckling of the paper surface as shown in Figure 2.

Laser printers use heat to melt a solid powder (toner) onto the paper, therefore, standard office paper must be able to withstand the high level of heat generated by the fuser rollers without warping or melting. Laser certified printer papers are quite resistant to high temperatures and are usually uncoated since any coating could melt in the printer, destroying the sheet and possibly ruining the printer.

Plain white bond that is certified for laser printing is the most common stock used universally in offices and by individuals. Toner bonds best to smoother and whiter surfaces, resulting in finer details and better clarity. Less expensive, courser papers can deposit lint in the printer, so it’s advisable to avoid uncertified bargain sheets.

In the past few years, many general-purpose SOBs of weights 21 to 27 lb. have been reformulated to work equally well with both inkjet and laser printers. Be warned though that these papers are only suitable for printing text, because of its lighter ink load.

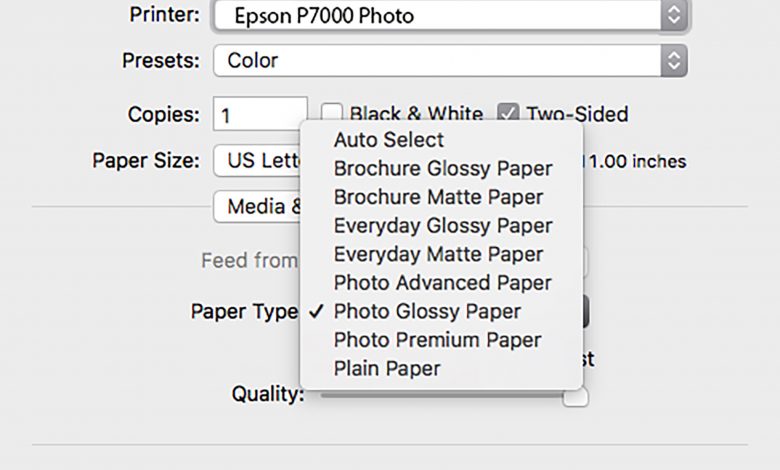

For all types of paper, printer driver settings should be configured to suit the specific paper so that the printer deposits the correct quantity of ink (see Figure 3).

Inkjet and Large-Format Paper

Paper designed for inkjet and large format printing are of better quality. Categorized by its weight, brightness, texture and opacity, inkjet papers require dimensional stability and adequate surface strength. Smoothness and limited porosity is also necessary to counteract excessive dot gain (see Figure 4).

Quality paper grades are frequently coated. For matte inkjet papers, silica is used as pigment in a medium of polyvinyl alcohol. Glossy inkjet papers are made by applying multiple coats of silica, or coating the substrate with polymer resin that imparts specific qualities to the paper including weight, gloss, smoothness and reduced ink absorbency.

Various materials, including kaolinite, (a type of clay), calcium carbonate, bentonite (absorbent aluminum phyllosilicate clay) and talc can be used to coat paper for high quality printing. The coating material (called “china clay”), is bound to the paper with synthetic viscosifiers such as styrene-butadiene latexes and natural organic binders such as starch. The coating formula may also contain chemical additives that evenly disperse the coating, or polymer resins to enhance water resistance and wet strength. These resins also increase the longevity of the print and help stabilize the ink against ultraviolet radiation.

Fine Art Papers

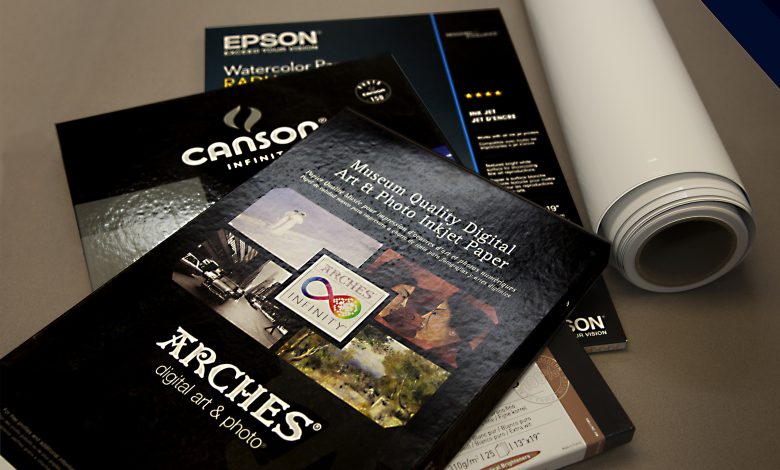

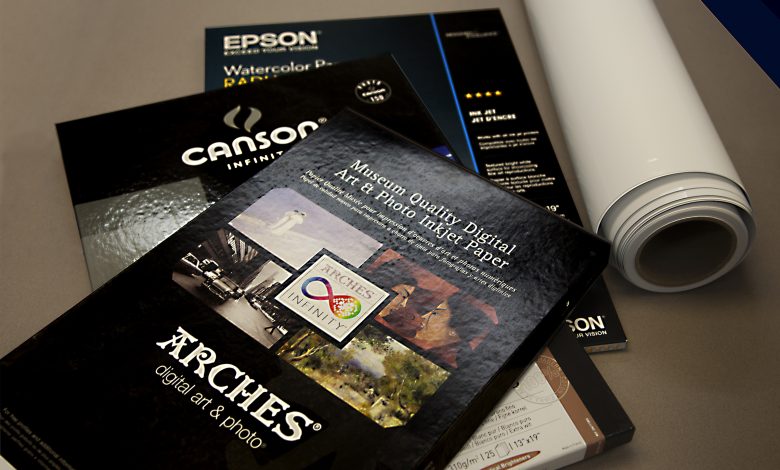

Fine art inkjet papers are manufactured for the professional photographer and artist. These papers are similar to traditional watercolor, printmaking, and photographic papers. They differ however because they are coated with resins and clays that are engineered to receive and hold ink. They meet similar standards for longevity and durability as traditional fine art papers and are usually “archival” meaning that they have a neutral pH and are free of lignin and optical brighteners. Fine art inkjet printing requires that the paper have perfect amount absorbency to accept the ink and prevent excessive ink spread.

Fine art papers are usually made of 100% cotton rag pulp. Some fine art papers are mold made, while others are machine made, and may vary considerably in surface texture. They are available in several surfaces including smooth, lightly textured, rough and even canvas (see Figure 5). Fine art papers, like most quality inkjet papers, can be purchased in either cut sheet sizes or in rolls from 8.5″ to 72″ wide (or larger), and up to 300′ long (see Figure 6).

Inkjet Photo Paper

Certain papers on the market are specifically formulated for printing photographs. These papers are usually bright white. To obtain maximum whiteness they are either bleached, or coated with pigments such as titanium dioxide. They can also be coated with a highly absorbent refined clay that limits ink spread.

Many of these papers, when printed with archival pigment-based inks, are equal to or can exceed the image quality and longevity of traditional photographic continuous tone printing.

Photo paper is typically categorized by its surface texture: glossy, semi-gloss, satin, semi-matte, and matte finishes. Paper thickness can vary. Higher-quality photo papers are thicker and have advanced coatings that sometimes enhance drying time. They are usually coated on one side. Glossy photo paper has a shiny finish. It is smooth and has a high degree of reflectivity. Matte photo paper is not shiny and has a slightly textured feel to the touch (see Figure 7).

Glossy inkjet papers produce the best color density and the widest color gamut. Photo papers vary in their longevity and their color gamut capacity. Ink suppliers frequently provide color profiles for their ink systems when used with specific papers. Longevity of a print depends on the specific combination of inks and paper, but it also depends on local environmental conditions. Exposure to heat, moisture and sunlight light can fade an archival print over time, no matter what paper it’s printed on.

Presentation Paper

Lighter weight, inkjet paper-sometimes called presentation paper-is not much different from standard office bond except it can be can be used for all types of printing. These papers are less expensive and of lesser quality. I suggest they be used for proofing only.

Paper Weights

This section is not about the heavy object you place on a stack of bills to prevent the wind from blowing them away. No, the weight, or thickness of paper is a critical consideration when printing. Heavier media often conveys higher quality and increases the strength and durability of the print. A common method for determining the weight of paper is called U.S. Basis Weight that categorizes paper into specific classes, the most common designations being: Bond, Text, Book, Index, Cover, Tag and Offset.

The U.S. Basis Weights system can be perplexing. Higher numerical values don’t always mean that the stock is heavier or thicker. For example, an 80 lb. text paper is not the same as 80 lb. cover, for instance-it is much lighter weight.

The basis weight is defined as the weight of 500 sheets of paper in its uncut “parent sheet” size, before being cut to standard letter, legal or tabloid sizes. An uncut sheet of bond paper is 17″ x 22″, while an uncut sheet of cover stock is 20″ x 26″. If 500 sheets of bond paper (17″ x 22″) weigh 20 lbs., then a ream (500 sheets) of paper cut to letter size will be labeled as 20 lb. bond. And if 500 sheets of cover paper (20″ x 26″) weigh 65 lbs., a ream of this paper trimmed to tabloid size would be marked as 65 lb. cover.

Only with papers that share the same basic sheet size, can weights be compared. When shopping for paper, if you see reams of bond paper identified as 17 lb., 20 lb. and 26 lb. paper, you can be confident that the 26 lb. paper is thicker and no doubt more costly than the other choices.

Paper Management

Here are a few tips for managing and storing inkjet paper and prints that will help you use this medium most efficiently and help prevent waste.

- Store your paper sheets in a temperate, dry environment, flat, not upright to prevent warping and curling.

- Download the ICC profiles from the paper manufacturer to produce the most reliable color.

- If your printer requires you to use different black ink for matte vs. glossy or satin paper, swap cartridges if necessary.

- If you are using matte or fine art papers with pigment-based inks, sandwich an interleaving tissue between the prints for storage. Black and darker pigment inks can sometimes rub off and scuff easily on matte and cotton papers.

- Whenever possible, gang prints destined for the same type of paper to save time and reduce scrap size.

- Use smaller sheets cut from larger rolls when there is excess. Your large-format printer can handle a multitude of sizes, so save your scraps if they are of reasonable size.

- Mat your archival prints with archival, one hundred percent cotton, acid-free mat board to prevent yellowing and deterioration over time.

- Store prints in plastic bags or sleeves made from biaxially oriented polypropylene. Avoid using any materials that contain polyethylene or plasticizers that can yellow your paper.